The patron: Hans Jakob Fugger

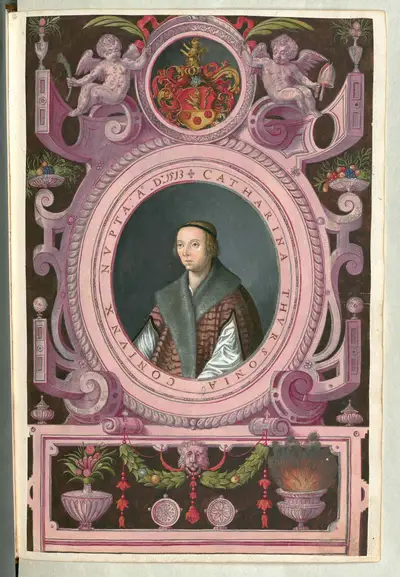

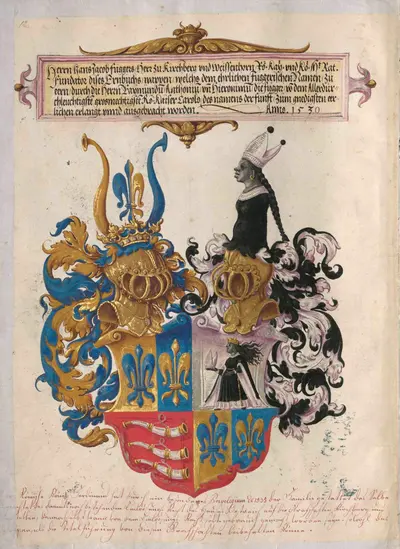

Hans Jakob Fugger (Augsburg 1516–München 1575) , who commissioned the Magnum ac Novum Opus, was Jacopo Strada’s earliest patron and – next to the Emperors Ferdinand I and Maximilian II - also the most important. He was born into the famous Augsburg banking family whose money had secured Charles V. accession to the Holy Roman Empire. Extremely privileged, he was also very gifted, and made full use of the excellent humanist education he received, which was in part directed by Viglius van Aytta van Swichem, the later chancellor of Charles V. His father was Raymund Fugger; his mother, Katharina Thurzo von Bethlemfalva, belonged to a Polish-Hungarian family that were the Fuggers’ closest business partners in that region.

Raymund was primarily an intellectual, who left the running of the firm to his brother Anton, concentrating on his library and collections, which he freely shared with the Augsburg sodalitas of humanist friends, of whom Konrad Peutinger was the most important. This circle incited Hans Jakob’s intellectual interests –primarily historical, political and antiquarian– which he developed during his academic peregrinations in France and Italy. He studied Roman law with Andrea Alciati, the academic superstar of his generation, and made friends with many fellow students who became very influential in later life –such as Cardinals Farnese, Granvelle, Madruzzo, and Truchsess von Waldburg, and Georg Sigmund Seld, afterwards Imperial Vice-Chancellor.

After the early death of his father in 1535, Hans Jakob had to return to Augsburg, to be trained to assume his eventual function as a director of the firm, traveling widely in Europe to visit the various Fugger branches, and also spending time at the secondary Habsburg court in Innsbruck, as a companion to King Ferdinand’s children, who were educated there.

Because of their close connections to Charles V, his uncle and mentor Anton Fugger and Hans Jakob himself played an important role in saving Augsburg from the consequences of having opted for the losing side in the war of the Schmalkaldic League, and Hans Jakob assumed political functions in Augsburg after the famous “geharnischter Reichstag” of 1548. The Fugger’s financial connections with the Habsburg would turn sour, when around 1560 Philip II suspended repayment of the immense loans he had obtained from them, which –in combination with Hans Jakob’s lavish intellectual patronage– finally led to his personal bankruptcy.

By this time Fugger had become a close personal friend and counsel of Duke Albrecht V of Bavaria, ten years his junior, whom he stimulated and supported both in his political views and in his cultural patronage. The Duke helped Fugger by paying off his debts in return for the huge library and collection that Fugger has assembled ever since he was a student, which became the founding stock of the Munich court library and the Kunstkammer. The development of library and collections, and the construction of specially designed buildings to house them -the Munich Münzhof for the Kunstkammer, and the Antiquarium for the collection of ancient sculptures and the library- were largely directed by him.

Hans Jakob had been collecting and commissioning books and manuscripts, and probably other materials, especially of historical and antiquarian interest since his student days, incited by the example of his father and the Augsburg humanist circle, and stimulated by his teachers, such as Alciati, and his many intellectual associates. His library was set up as an encyclopaedic storehouse of knowledge, modelled on Bibliotheca Universalis (printed Zürich 1545), the first general bibliography ever, created by the Swiss humanist, lexicographer and botanist Conrad Gessner. Failing to persuade Gessner to come to Augsburg to be his librarian, Fugger used the system of the Bibliotheca to organise his library, which was institutional, rather than private in concept, ambition and scope.

Like the Augsburg humanists, and like Alciati and Gessner, Fugger was very much aware of visual documentation – epistemic images – as sources of concrete information. His association with Jacopo Strada, an Italian artist and antiquary resident in Nuremberg whom he employed at the latest since 1544, must have stimulated his own ideas in this field. Strada had been trained in the circle of Giulio Romano, a pupil of Raphael and one of his collaborators in a project to document the remains of Ancient Rome. Through Strada and through his other contacts in Rome, Fugger was probably aware of the work of an informal “Vitruvian Academy’, consisting of prelates, men of letters and artists, which aimed to study physical remains of Roman civilization both from scholarly motifs, and to restore the arts, especially architecture, to its ancient splendour. This project explicitly included documenting ancient inscriptions and coins for the information these provided on the history and the institutions of the ancient world.

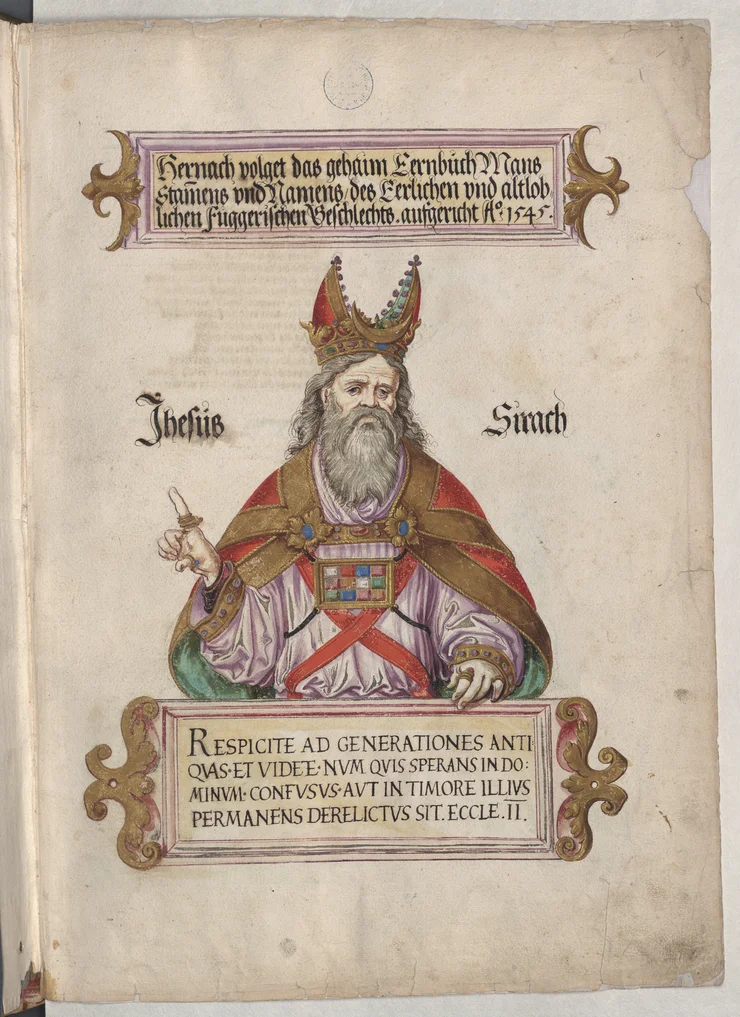

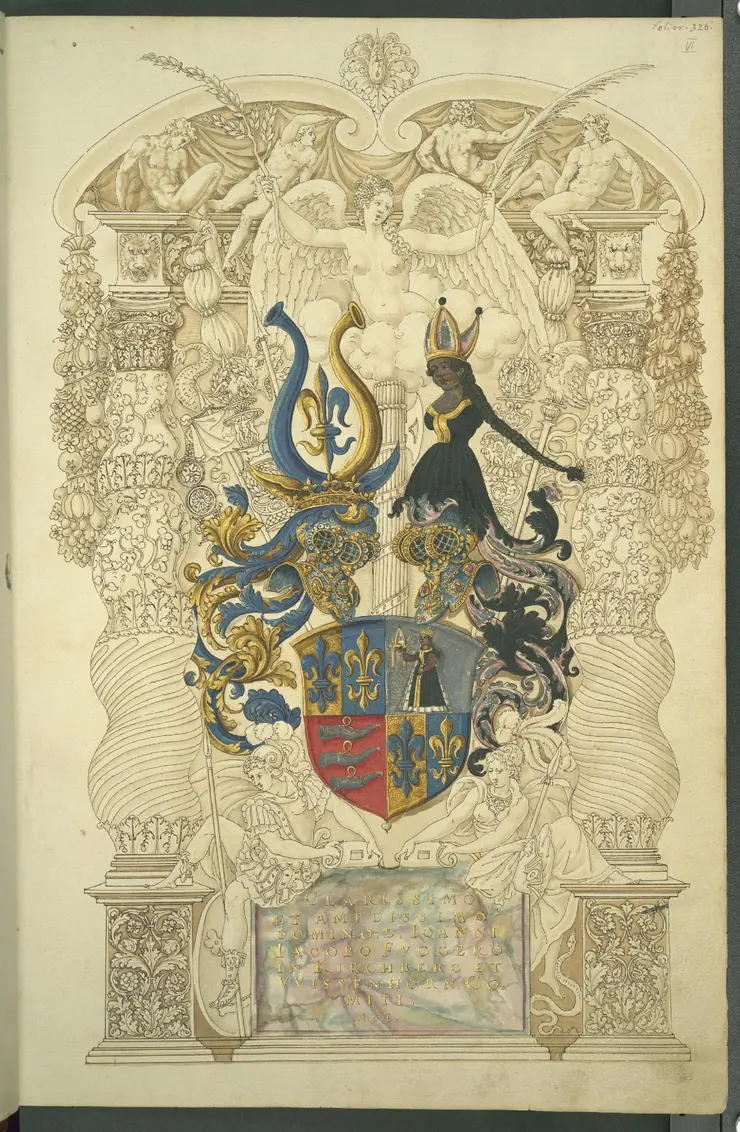

Fugger commissioned various works including large quanties of images, intended as documentation, rather than as works of art, such as the Ehrenbuch which presented the genealogy and history of his own family, including innumerable portraits and coats of arms, of the so-called Ehrenspiegel Österreichs, a similar huge compendium documenting the history an genealogy of the Habsburg dynasty.

But Fugger’s interest transcended his own family, Augsburg, and even the one imperial dynasty to which his family was so closely connected. Thus he commissioned a huge number of grand folio albums documenting the coats of arms of princes, prelates, city-states and noble families of Italy, all in illuminated drawings provided by Strada’s workshop.

Producing such “libri di disegni”, collection of visual documentation, appears to have been an important acitivity of the Strada workshop. In view of his antiquarian expertise, it was natural that Fugger would entrust him with both the research and the execution of what was promising to become his most important commission: the huge corpus of numismatic drawings assembled by Jacopo Strada and his workshop, entitled Magnum ac novum opus continens descriptionem vitae, imaginum, numismatum omniumvtam Orientalium quam Occidentalium Imperatorum usque ad Carolum / V. Imperatorem. That is: A Great and New Work Containing Descriptions of the Lives, and Images of the Coins, of all Emperors<..> of the Eastern and the Western Empire <…> up to the Emperor Charles V.

In view of Fugger’s humanist interest and his personal involvement in other prestigious commissions, such as the Ehrenspiegel Österreichs, where he instructed, supervised and corrected its author, Clemens Jäger, in person, it is likely that the concept of the Magnum ac Novum Opus was worked out by Strada and Fugger together. The choice to concentrate on the coins of the Roman Emperors, which was becoming a trendy topic, may have been Fugger’s choice, inspired by the earlier documented by Kornad Peutinger, his father’s friend, in his manuscript “Kaiserbuch”. It tallied with his political affiliation with the Holy Roman Emperors, considered the successors of the Roman Emperors, and his preference for the monarchy grounded in Roman law, which he had studied under Alciati.

It has not yet been possible to clarify whether Fugger commissioned, owned a copy of or if there even was a patron for the coin descriptions A ∙ A ∙ A ∙ / Numismatωn antiquorum Διaσκευη, hoc est, Chaldaeorum <…> Graecorum <…> ac <…> Romanorum Regum <…> , Coss. tempore Reipublicae, & <..> tam sub Caess. Latinis, in occidente, quam Graecis Impp. / in oriente, declinante Imperio <..> metallicarum eico num /explicatio. That is:

Instrument of Ancient G[olden], S[ilver] and B[ronze] Coins: that is, Explanation of the metal images of the Chaldean, <…> Greek, <…> as well as <…> Roman Kings, <…> Consuls from the time of the Republic and hitherto, both under the Latin Caesars, in the West, and under the Greek Emperors, in the East; and then when the Empire of the Roman people was in decline <…> .

When Fugger’s collections were ceded to Duke Albrecht V. of Bavaria, who took on Fugger’s debts in exchange, Fugger himself came with them to Munich as a personal councillor of the Duke. Appointed Musikintendant – managing director of the music at court, next to the Kapellmeister Orlando di Lasso as “artistic director”, in fact he oversaw most of the cultural initiatives at court: this in addition to his political advice and his role in reorganising the Hofkammer, the financial administration of the Dukedom, resulting in his appointment as Hofkammerpräsident in 1573. When he died two years later, the Duke took on all the expenses of his funeral, including the transfer of his body to his family tomb in the Augsburg Dominikanerkirche.

Further reading:

- Otto Hartig, Die Gründung der Münchner Hofbibliothek durch Albrecht V. und Johann Jakob Fugger, [Abhandlungen der Königlich Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Phil. Hist. Kl. 28 , Abhandlung 3], München 1917, pp. I–XIV and pp. 1–442.

- Wilhelm Maasen, Hans Jakob Fugger (1516–1575): Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des XVI. Jahrhunderts, München/Freising 1922.

- Dirk Jacob Jansen, Jacopo Strada and Cultural Patronage at The Imperial Court: The Antique as Innovation, 2 vols. [Rulers & Elites: Comparative Studies in Governance 17/1–2], Leiden/ Boston 2019; Open Access https://brill.com/downloadpdf/title/35818, Ch. 3.