"Not everywhere that says inclusion on it is inclusion in it!"

Current topics such as war, Corona and digitalisation are currently pushing inclusion into the background as a permanent task not only for schools, but also in university research and teaching. This makes a contribution on the occasion of the upcoming anniversary of the entry into force of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in Germany all the more important. What exactly does the Convention mean for German schools? Where do we stand here in the implementation of inclusion?

The significance for the German school system is anchored in Article 24 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN CRPD). The focus is on participation and equal opportunities, which are not only to be fulfilled for people with disabilities. An inclusive education system also takes into account other dimensions of heterogeneity such as age, origin, education, ethnicity, sexuality and religion. With regard to disability, both visible and hidden needs for support should be adequately taken into account through appropriate inclusive social and organisational development. The Conference of Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs (KMK) has defined the following special educational needs for schools: vision (Sehen, SE), hearing (Hören, H), physical-motor development (körperlich-motorische Entwicklung, KME), intellectual development (geistige Entwicklung, GE), learning (Lernen, L), emotional-social development (emotionale-soziale Entwicklung, ESE) and language (Sprache, S).

In the German "school landscape" there are, on the one hand, federal states which, in addition to schools with the profile of inclusion, also provide a differentiated special school system, such as Bavaria in the very costly twin-track model. On the other hand – as for example with the Thuringian community school and the educational pathways Primary schools (grades 1-4)/ secondary schools (grades 5-9/10) – attempts are being made to develop as many schools as possible as inclusive schools and, in most cases, also as all-day institutions (with the exception of the focus on GE). In general, there are also special vocational schools as well as schools for the (chronically) ill or partly also with a focus on autism spectrum disorders (ASD). In order to cover all support needs at schools, Mobile Special Education Services (MSD) can also be requested supraregionally with their expertise. With regard to the percentage of inclusive and exclusive schooling, a slowly but continuously increasing trend can be observed. Nationwide, 44.5% of pupils with special educational needs are taught in general schools (KMK, 2022). Taking into account the different support needs, large differences can be observed: L, S, ESE with an almost 50:50 distribution, GE predominantly (85.9%) in special schools. Thuringia is almost exactly in line with this national average and offers 46% of pupils with special educational needs education in general schools. 54% – and this is statistically still the majority – remain in special schools and are thus excluded.

Not everywhere that says inclusion on it is inclusion in it!

However, the development of an inclusive education system at all levels does not depend on the usually declared quantitative implementation, but above all on the quality of inclusion. This, in turn, must be carefully examined and scientifically monitored, as good quality inclusion requires material and human resources. If these preconditions are not met – e.g. due to austerity policies or a lack of investment in the education sector – inclusion cannot succeed. Here, the so-called quality-exclusivity dilemma becomes apparent in that only a few "exclusive" schools also have a high quality of inclusion, which, however, have a model function as best-practice examples.

According to the pronouncements of the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs of the Länder in the Federal Republic of Germany (Kultusministerkonferenz), the core task for teachers is the targeted planning, organisation and reflection of teaching and learning processes based on scientific findings, as well as their individual assessment and systemic evaluation. So when we look at implementation processes in inclusive schools, we must also ask how teachers are currently trained. Here, the universities are making many efforts to further develop their degree programmes in an inclusive way. The various projects from the Quality Initiative for Teacher Education, such as QUALITEACH at the University of Erfurt, have made a significant contribution to this. Student teachers should prepare themselves for the following areas of responsibility:

- Educating and teaching, also in team teaching (TT),

- Diagnosing and supporting,

- evaluating, assessing and advising,

- in-service training for themselves and others,

- (inclusive) school development and innovation,

- interdisciplinary cooperation, networking and, in the best case, (district) political engagement.

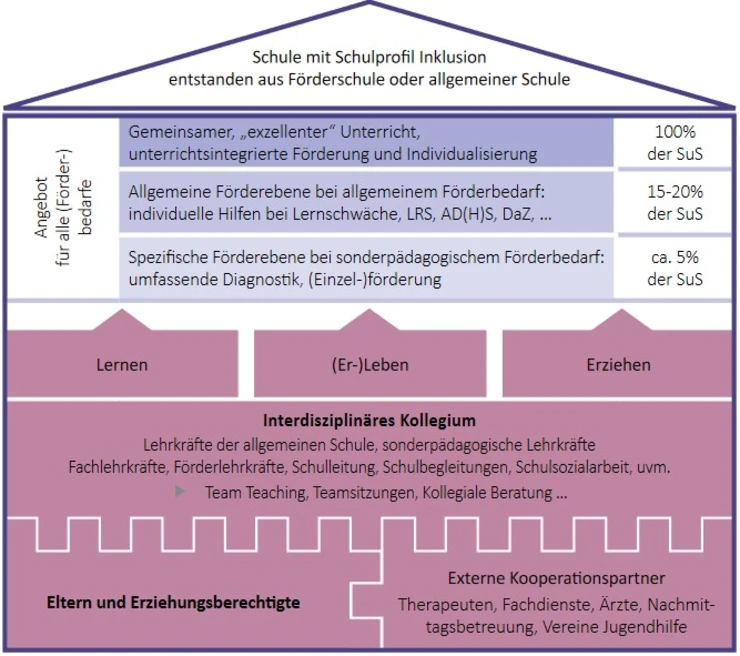

With regard to prevention, three different levels of support can be distinguished in the school context based on the so-called Response-To-Intervention (RTI) approach: In the first support level, "excellent" joint teaching is anchored, which integrates individual measures. At support level two, additional small group support is added, and at the third support level even intensive individual support. For further reading, I recommend the "Studienbuch Inklusion" published by Heimlich & Kiel (2020). The illustration (see right) is also taken from this book and shows a possible school development process in concrete terms: The individual needs or support needs of the children and young people are at the centre of the development process, followed by the quality of cooperation within the multi-professional team and with the parents as well as the school concept and school life. Furthermore, networking with the environment in the course of external cooperation is of great importance.

As a conclusion, I would like to state that the duty to develop and implement an inclusive education system on all levels also in Germany according to the UN CRPD is still a permanent, process-accompanying matter to be carried out in small steps. For a "real" democracy, freedom, equality of opportunity and diversity are not only to be valued, but also to be lived together, reflected upon and internalised as an attitude. Despite the current difficulties related to politics and society, the vision or goal of an inclusive (high) school landscape should promote a sense of purpose and commitment.